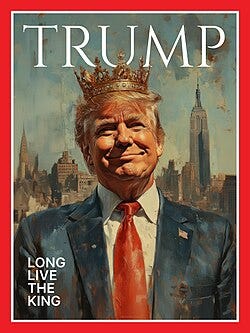

Q&A: Two Scholars Trace The Rise of the 'Strongman' Presidency

A conversation with political scientists William Howell and Terry Moe about how U.S. presidential power has grown to enable a strongman

Terry Moe is the William Bennett Munro Professor of Political Science at Stanford University and William Howell is inaugural Dean of the Sch…