Q&A: A Historian Immersed Himself in Russia's 'Fascist' Online Groups. Here's What He Found.

Dr. Ian Garner spoke to dozens of young Russians, many of whom have become hardcore nationalists since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

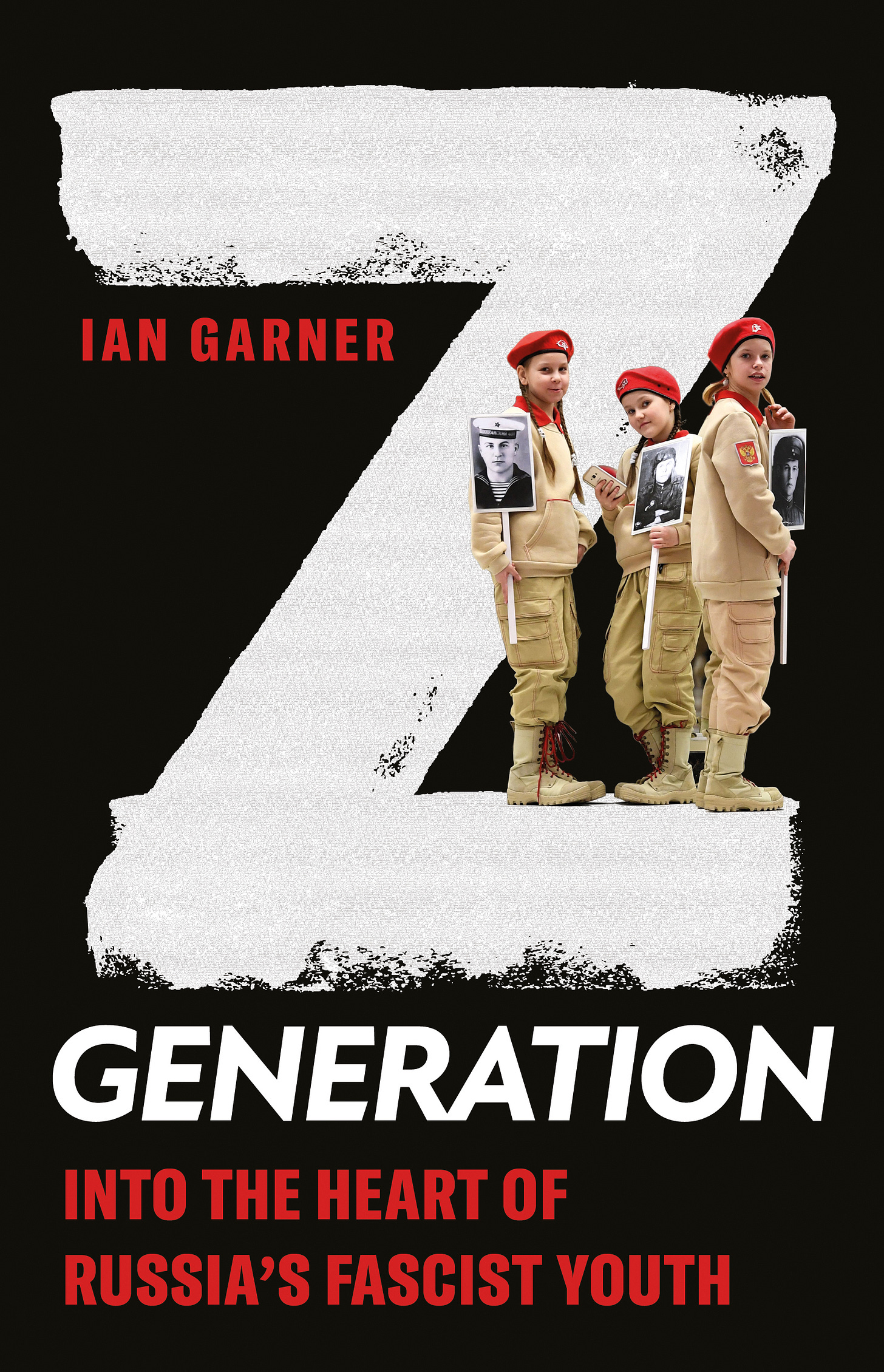

Dr. Ian Garner is a historian and analyst of Russian culture and war propaganda based in Kingston, Ontario. He is the author of the new book, Z Generation: Into the Heart of Russia’s Fascist Youth. (…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Public Sphere to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.