June 4 was the most important day of 1989

Why we should look to Poland and fear China

Looking back at the revolutions of 1989, many people think of the fall of the Berlin Wall on November 9 as a symbol for the entire year. Indeed, it was a dramatic moment, just a few miles from where I am sitting now. However, reflecting 35 years later, June 4, 1989 was a more consequential day.

On that day, Poland held its first partly free elections in over 40 years, which was the beginning of the end of its communist dictatorship. Meanwhile, in Beijing, the Chinese government opened fire on pro-democracy protesters, killing hundreds, if not thousands. These events illustrate how autocracies can either end peacefully or muddle through with horrible violence. Moreover, they show that 1989 was less of an inevitable "end of history" when liberal democracy won out than it was a moment when history changed based on decisions made by human beings.

Going into 1989, Poland's communist government was under pressure. The economy was tanking and Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev had indicated that he would not intervene in Eastern Europe. The Polish government initiated talks with the Solidarity movement, in an attempt to defuse the banned popular trade union and make it share some of the burden of painful economic reforms. The result was the Round Table Agreement of April 6, which legalized trade unions, established a presidency and parliament known as the Sejm, and allowed for a free press.

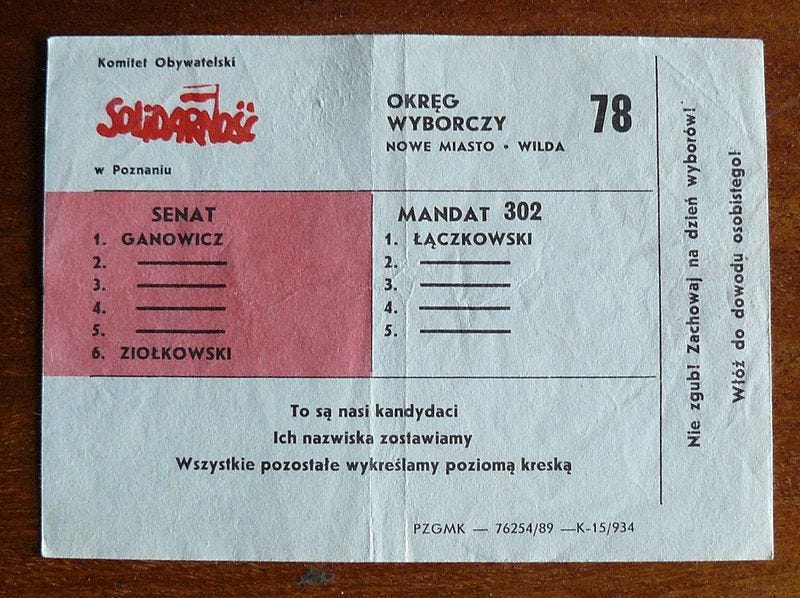

Elections were held on June 4, with a compromise of 35 percent of 460 Sejm seats being freely contested and 65 percent reserved for communists and their allies. The Senate, with far less power, had all of its 100 seats up for grabs. Many observers predicted a mixed result or even a communist win. However, Solidarity won all of the contested Sejm seats and all but one of the Senate seats.

In the spring of 1989, the Chinese leadership was divided over whether to negotiate or crack down on the largest demonstrations in the 40 years of its communist regime. On May 20, the People’s Liberation Army attempted to occupy Beijing, but protesters overwhelmed them and they had orders not to fire. The army eventually left, but the Chinese government was humiliated. The regime declared martial law on June 3, and on June 4, the PLA entered Tiananmen Square, which had been the center of the pro-democracy protests. It later opened fire on protesters who refused to leave, injuring and killing thousands.

Looking backwards, it can seem like these events were predestined. However, at the time, there were reasons to think that the opposite might happen.